THE INDUSTRIAL DISPUTE ACT, 1947

INDUSTRIAL DISPUTE ACT, 1947

This Act applies to workers carrying out manual, unskilled, technical, operational or supervisory work and does not apply to workers earning more than Rs.1,600 per month carrying out managerial work. In addition, the worker must have had continuous service of at least one year.

It provides for the conciliation and adjudication of industrial disputes by Conciliation Officers, a Board of Conciliation and Court of Inquiry, Labor Courts, Industrial Tribunals and a National Industrial Tribunal. Each has a different jurisdiction or purpose, except for Conciliation Officers, whose jurisdiction is more general. Industrial dispute means any dispute or difference between employers and employers, or between employers and workmen, or between workmen and workmen, which is connected with the employment or non-employment or the terms of employment or with the conditions of labor, of any person. Industrial disputes include cases of unfair dismissal.

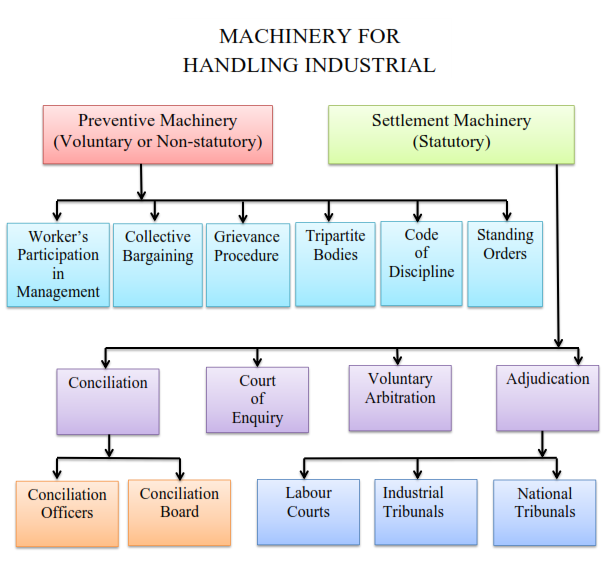

Machinery for resolving Industrial Disputes under Law

This machinery has been provided under the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947. It, in fact, provides a legalistic way of setting the disputes. As said above, the goal of preventive machinery is to create an environment where the disputes do not arise at all.

Conciliation:

It refers to the process in which representatives of employees and employers come together to a third party in a view to discuss the dispute and reconcile their differences and conclude to an agreement by mutual consent.

In this process the third party known as a facilitator. In this type of dispute, the state intervenes for the settlement process. This act gives power to the Central & State Government in order to appoint an officer known as conciliation officer and board for conciliation whenever circumstance needed. The duties of a conciliation officer are:

- To conduct proceedings of conciliation in a view to conclude the settlement between concerned parties amicably.

- Send the settlement report and a memorandum to the appropriate government.

- Send a report to the government regarding what steps taken by him in case the process of settlement does not come to an end.

- However, the officer for conciliation cannot force for a settlement. He can only request and support the parties to conclude an agreement. The Industrial Disputes Act restricts strikes and deadlocks during the ongoing proceedings of conciliation

(i)CONCILIATION OFFICERS (Sec 4)

The appropriate Government may appoint such number of persons as it thinks fit, to be conciliation officers, by notification in the Official Gazette. A conciliation officer may be appointed for specified industries in a specified area or for one or more specified industries and either permanently or for a limited period. Duties of Conciliation Officers:

- In every industrial dispute, existing or apprehended, the conciliation officer shall hold the conciliation proceedings in prescribed manner.

- The conciliation officer for settling the dispute without delay shall investigate the dispute and may do all such things to make the parties to come fair and amicable settlement of dispute.

- The conciliation officer shall send a report on the settlement o f the dispute to the appropriate Government together with a memorandum o f the settlement signed by the parties to the dispute.

- If no such settlement is arrived at, the conciliation officer shall as soon as practicable after the close o f the investigation, send to the appropriate Government a full report setting forth the steps taken by him for ascertaining the facts and circumstances relating to the dispute, and bringing about a settlement thereof together with a full statement of such facts and circumstances and the reasons on account of which, in his opinion, a settlement could not be arrived at.

- If, on a consideration o f the failure report referred above the appropriate Government is satisfied, that there is a case for reference to a Board, Labour Court, Tribunal or National Tribunal it make such reference. Where the appropriate Government does not make such a reference it shall record and communicate to the parties concerned its reasons thereof

- A report under Sec. 12 shall be submitted within 14 days o f the commencement of the conciliation proceedings or within such shorter period as may be fixed by the appropriate Government..

(ii) BOARD OF CONCILIATION (SEC.5)

The appropriate Government may as the occasion arises by notification in the Official Gazette constitute a Board of conciliation for promoting the settlement of an industrial dispute. A Board shall consist of Chairman and two or four other members, as the appropriate Government thinks fit. The Chairman is an independent person and other members are representatives o f the parties to the dispute in equal numbers. Duties of Board of Conciliation (Sec 13):

- Where the dispute has been referred to a Board under this Act, it shall he the duty of the Board to Endeavour to bring about at settlement of her same and for this purpose the Board shall, in such manner as it thinks fit and without delay, investigate the dispute and all matters affecting the merits and the right settlement thereof and may do all such things as it thinks fit for the purpose of inducing the parties to come to a fair and amicable settlement of the dispute .

- If a settlement of dispute or of any of the matters in dispute is arrived at in the course of the conciliation proceedings the Board shall send a report thereof to the appropriate Government together with a memorandum o f the settlement signed by the parties to the dispute.

- If no such settlement is arrived at, the Board shall as soon as practicable after the close o f investigation send to the appropriate Government a full report on the steps taken by the Board for ascertaining the facts and circumstances relating to the dispute and for bringing about a settlement thereof Report shall also contain a full statement o f such facts and circumstance and the reasons on account of which, in its opinion a settlement could not be arrived at.

2. Court of Inquiry:

In case of the failure of the conciliation proceedings to settle a dispute, the government can appoint a Court of Inquiry to enquire into any matter connected with or relevant to industrial dispute. The court is expected to submit its report within six months. The court of enquiry may consist of one or more persons to be decided by the appropriate government.

The court of enquiry is required to submit its report within a period of six months from the commencement of enquiry. This report is subsequently published by the government within 30 days of its receipt. Unlike during the period of conciliation, workers’ right to strike, employers’ right to lockout, and employers’ right to dismiss workmen, etc. remain unaffected during the proceedings in a court to enquiry.

A court of enquiry is different from a Board of Conciliation. The former aims at inquiring into and revealing the causes of an industrial dispute. On the other hand, the latter’s basic objective is to promote the settlement of an industrial dispute. Thus, a court of enquiry is primarily fact- finding machinery.

1. Voluntary Arbitration:

On failure of conciliation proceedings, the conciliation officer many persuade the parties to refer the dispute to a voluntary arbitrator. Voluntary arbitration refers to getting the disputes settled through an independent person chosen by the parties involved mutually and voluntarily.

In other words, arbitration offers an opportunity for a solution of the dispute through an arbitrator jointly appointed by the parties to the dispute. The process of arbitration saves time and money of both the parties which is usually wasted in case of adjudication.

Voluntary arbitration became popular as a method a settling differences between workers and management with the advocacy of Mahatma Gandhi, who had applied it very successfully in the Textile industry of Ahmadabad. However, voluntary arbitration was lent legal identity only in 1956 when Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 was amended to include a provision relating to it.

The provision for voluntary arbitration was made because of the lengthy legal proceedings and formalities and resulting delays involved in adjudication. It may, however, be noted that arbitrator is not vested with any judicial powers.

He derives his powers to settle the dispute from the agreement that parties have made between themselves regarding the reference of dispute to the arbitrator. The arbitrator should submit his award to the government. The government will then publish it within 30 days of such submission. The award would become enforceable on the expiry of 30 days of its publication.

Voluntary arbitration is one of the democratic ways for setting industrial disputes. It is the best method for resolving industrial conflicts and is a close’ supplement to collective bargaining. It not only provides a voluntary method of settling industrial disputes, but is also a quicker way of settling them.

Pros and cons of Arbitration in Industrial Disputes

- It is established by the parties and therefore both parties have conveyed their faith in the process of arbitration.

- Nature is a flexible and informal process.

- The concept is based on mutual consent of the parties and hence, therefore, it helps for healthy industrial functions and relations.

- Delay for settlement of disputes often occurs.

- The arbitration process is expensive and all the expenses are to be incurred by both labours and the management equally.

- When the arbitrator becomes biased and if he is incompetent then the Judgment becomes arbitrary.

- Adjudication:

It is the final legal option for settlement of Industrial Dispute. It means a legal authority appointed by government who intervenes in order to make a settlement which is binding on both the parties.

In other words, a settlement of an Industrial dispute by a labor court or a tribunal is mandatory. For the process of adjudication, the Act provides a piece of 3-tier machinery.

(i)Labor Court

For the adjudication of industrial disputes relating to the specified matters in the second schedule of the act, the appropriate government may by notification constitute one or more labor court. Powers of labor courts are:

- Discharge or grant of relief to workmen who are wrongfully employed or dismissed.

- To determine the illegality of a strike or deadlocks.

- Customary concession or privileges are withdrawn by this court.

- Within the specified period the order referring to the dispute, its report is to be submitted to the appropriate government, whenever an industrial dispute adjudicating by the labour court.

(ii) Industrial Tribunal

For the adjudication of the industrial disputes, the appropriate government may, by notification constitute one or more industrial tribunals. Matters relating to the following are:

- Retrenchment of labor.

- Compensatory and other allowances and rules of the disciple in the workplace.

- If the company is in profit, then matter related to bonus and profit sharing.

- Work manual such as hours of working and interval for rest.

- Wages and provident fund of workmen.

- The duty of the Industrial Tribunal to hold its proceedings fast and submit its report to the state government within the specified time given.

(iii)National Tribunal

The central government may, by notification in the official Gazette, constitute one or more National Tribunals for the adjudication of Industrial Disputes in:

- National matters.

- Matters in which industries are more than one state, or are affected by the outcome of the dispute.

- The duty of the National Tribunal to hold its proceedings fast and submit its report to the central government within the specified time given

Some of the major preventive machinery for handling industrial disputes in India are as follows:

- Worker’s Participation in Management

- Collective Bargaining

- Grievance Procedure

- Tripartite Bodies

- Code of Discipline

- Standing Orders.

1. Worker’s Participation in Management:

It is a method whereby the workers are allowed to be consulted and to have a say in the management of the unit. The important schemes of workers’ participation are: Works committee, joint management council (JMC).

2. Collective Bargaining:

Collective bargaining is the term used to describe a situation in which essential conditions of employment are determined by a bargaining process undertaken by representatives of a group of workers on the one hand and of one or more employers on the other. The role of collective bargaining for solving the issues arising between the management and the workers at the plant or industry level has been widely recognized.

3. Grievance Procedure:

Grievances are symptoms of conflicts in the enterprise. So, they should be handled very promptly and efficiently. Coping with grievances forms an important part of a manager’s job. The manner in which he deals with grievances determines his efficiency in dealing with the subordinates. A manager is successful if he is able to build a team of satisfied workers by removing their grievances. This would help in the prevention of industrial disputes in the organization.

- Tripartite Bodies:

Industrial relations in India have been shaped largely by principles and policies evolved through tripartite consultative machinery at industry and national levels. The aim of the consultative machinery is to bring the parties together for mutual settlement of differences in a spirit of cooperation and goodwill.

Indian Labor Conference (ILC) and Standing Labor Committee (SLC) have been constituted to suggest way and means to prevent disputes. The representatives of the workers and employers are nominated to these bodies by the Central Government in consultation with the All-India organizations of workers and employers.

5. Code of Discipline:

Code of Discipline is a set of self-imposed mutually agreed voluntary principles of discipline and good relations between the management and the workers in industry. In India, Code of Discipline was approved by the 16th Indian Labor Conference held in 1958.

It contains three sets of codes which have already been discussed later in this book. According to National Commission on Labor, the Code in reality has been of limited use. When it was started, very favorable hopes were thought of it; but soon it started acquiring rust.

6. Standing Orders:

The Standing Orders regulate the conditions of employment from the stage of entry in the organization of the stage of exits from the organization to prevent the emergence of industrial strife over the conditions of employment, one important measure is the Standing Orders.. Thus, they constitute the regulatory pattern for industrial relations. Since the Standing Orders provide

Do’s and Don’ts, they also act as a code of conduct for the employees during their working life within the organization.

STRIKES AND LOCKOUTS.

- A) GENERAL PROHIBITION OF STRIKES AND LOCKOUTS.

No workman who is employed in any industrial establishment shall go on strike in breach of contract and no employer of any such workman shall declare a lock-out–

- during the pendency of conciliation proceedings before a Board and seven days after the conclusion of such proceedings;

- during the pendency of proceedings before a Labor Court, Tribunal or National Tribunal and two months after the conclusion of such proceedings;

- during the pendency of arbitration proceedings before an arbitrator and two months after the conclusion of such proceedings; or

- During any period in which a settlement or award is in operation, in respect of any of the matters covered by the settlement or award.

- B) ILLEGAL STRIKES AND LOCK-OUTS.

- A strike or a lock-out shall be illegal if –

- it is commenced or declared in contravention of conditions specified in 7 above; or

- it is continued in contravention of an order made by the state Government after reference of Industrial disputes to the Board, Labor Court, Tribunal or National Tribunal under section 10 or after the reference under section 10A for arbitration;

- Where a strike or lock-out in pursuance of an industrial dispute has already commenced and is in existence at the time of the reference of the dispute to a Board, an arbitrator, a Labor Court, Tribunal or National Tribunal, the continuance of such strike or lock-out shall not be deemed to be illegal, provided that such strike or lock-out was not at its commencement in contravention of the provisions of this Act or the continuance thereof was not prohibited as specified in sub clause (ii) above.

- A lock-out declared in consequence of an illegal strike or a strike declared in consequence of an illegal lock-out shall not be deemed to be illegal.

- C) PENALTY FOR ILLEGAL STRIKES AND LOCK-OUTS.

- Any workman who commences, continues or otherwise acts in furtherance of, a strike which is illegal under this Act, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to one month, or with fine which may extend to fifty rupees, or with both.

- Any employer who commences, continues, or otherwise acts in furtherance of a lock-out which is illegal under this Act, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to one month, or with fine which may extend to one thousand rupees, or with both

- LAY-OFF OF WORKMEN

- A) PROHIBITION OF LAY-OFF

- No workman (other than a badli workman or a casual workman) whose name is borne on the muster-rolls of an industrial establishment in which not less than one hundred workmen were employed on an, average per working day for the preceding twelve months, shall be laid- off by his employer except with the prior permission of the State Government or such authority as may be specified by the State Government by notification in the Official Gazette, obtained on an application made in this behalf unless such lay-off is due to shortage of power or to natural calamity.

- An application for permission under sub-section (1) shall be made by the employer in the prescribed manner stating clearly the reasons for the intended lay-off and a copy of such application shall also be served simultaneously on the workmen concerned in the prescribed manner.

- Where an application for permission under sub-section (1) has been made the State Government or the specified authority, after making such enquiry as it thinks fit and after giving a reasonable opportunity of being heard to the employer, the workmen concerned and the persons interested in such lay-off, may, having regard to the genuineness and adequacy of the reasons for such lay-off, the interests of the workmen and all other relevant factors, by order and for reasons to be recorded in writing, grant or refuse to grant such permission and a copy of such order shall be communicated to the employer and the workmen.

- Where an application for permission under sub-section (1) has been made and the appropriate Government or the specified authority does not communicate the order granting or refusing to grant permission to the employer within a period of sixty days from the date on which such application is made, the permission applied for shall be deemed to have been granted on the expiration of the said period of sixty days.

- An order of the State Government or the specified authority granting or refusing to grant permission shall be final and binding on all the parties concerned and shall remain in force for one year from the date of such order.

Provided the State Government or the specified authority may, either on its own motion or on the application made by the employer or any workman, review its order granting or refusing to grant permission or refer the matter, or, as the case may be, cause it to be referred, to a Tribunal for adjudication. Where a reference has been made to a Tribunal under this sub-section, it shall pass an award within a period of thirty days from the date of such reference.

- Where no application for permission is made within the period specified therein, or where the permission for any lay-off has been refused, such lay-off shall be deemed to be illegal from the date on which the workmen had been laid-off and the workmen shall be entitled to all the benefits under any law for the time being in force as if they had not been laid-off.

- Notwithstanding anything contained in the foregoing provisions of this section, the State Government may, if it is satisfied that owing to such exceptional circumstances as accident in the establishment or death of the employer or the like, it is necessary so to do, by order, direct that the provisions of sub-section (1) specified above shall not apply in relation to such establishment for such period as may be specified in the order.

Explanation : For the purposes of this section, a workman shall not be deemed to be laid-off by an employer if such employer offers any alternative employment (which in the opinion of the employer does not call for any special skill or previous experience and can be done by the workman) in the same establishment from which he has been laid-off or in any other establishment belonging to the same employer, situate in the same town or village, or situate within such distance from the establishment to which he belongs that the transfer will not involve undue hardship to the workman having regard to the facts and circumstances of his case, provided that the wages which would normally have been paid to the workman are offered for the alternative appointment also.

- B) RIGHT OF WORKMEN LAID OFF FOR COMPENSATION

Whenever a workman (other than a badli workman or a casual workman) whose name is borne on the muster rolls of an industrial establishment and who has completed not less than one year of continuous service under an employer is laid off, whether continuously or intermittently, he shall be paid by the employer for all days during which he is so laid off, except for such weekly holidays as may intervene, compensation which shall be equal to fifty per cent of the total of the basic wages and dearness allowance that would have been payable to him had he not been so laid off :

Provided that if during any period of twelve months, a workman is so laid-off for more than forty-five days, no such compensation shall be payable in respect of any period of the lay-off after the expiry of the first forty-five days, if there is an agreement to that effect between the workman and the employer:

Provided further that it shall be lawful for the employer in any case falling within the foregoing proviso to retrench the workman in accordance with the provisions contained (as specified below) for retrenchment at any time after the expiry of the first forty-five days of the lay-off and when he does so, any compensation paid to the workman for having been laid-off during the preceding twelve months may be set off against the compensation payable for retrenchment.

- C) WORKMEN NOT ENTITLED TO COMPENSATION IN CERTAIN CASES

No compensation shall be paid to a workman who has been laid off –

- if he refuses to accept any alternative employment in the same establishment from which he has been laid off, or in any other establishment belonging to the same employer situate in the same town or village or situate within a radius of five miles from the establishment to which he belongs, if, in the opinion of the employer, such alternative employment does not call for any special skill or previous experience and can be done by the workman, provided that the wages which would normally have been paid to the workman are offered for the alternative employment also;

- if he does not present himself for work at the establishment at the appointed time during normal working hours at least once a day;

- If such lying off is due to a strike or slowing-down of production on the part of workmen in another part of the establishment.

- D) EMPLOYER TO MAINTAIN MASTER ROLLS OF WORKMEN

Notwithstanding that workmen in any industrial establishment have been laid off, it shall be the duty of every employer to maintain for the purposes of this Chapter a muster roll, and to provide for the making of entries therein by workmen who may present themselves for work at the establishment at the appointed time during normal working hours.